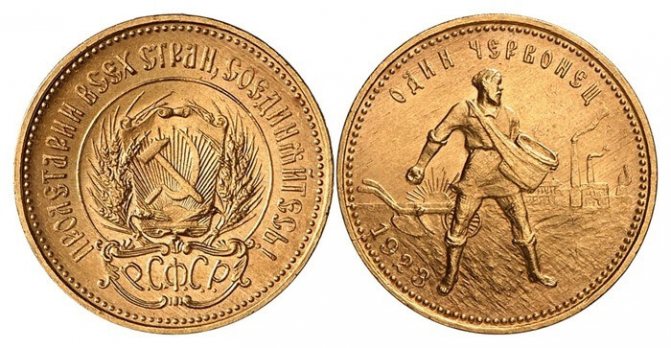

In October 1922, at the same time as the appearance of paper chervonets, a decision was made to issue gold coins of the same denomination. 10 rubles from the time of Nicholas II were chosen as a prototype. The diameter of the “Sower” was 22.6 mm, thickness – 1.7 mm, and weight – 8.603 g. The material was 900-carat gold.

The obverse was decorated with the coat of arms of the RSFSR, and on the reverse there was an image of a peasant sower, after whom the coin was named. The prototype of the image was the sculpture of I. D. Sharda.

On August 27, 1923, the Petrograd Mint began minting the “Sower” simultaneously with the 5th and 10th rubles of the tsar’s design (which, due to the shape of the tsar’s head, was called the “chervonets-light bulb”).

The purpose of minting a gold coin was the need to support the paper chervonets on the market. It was supposed to become an indispensable reserve, which, in case of urgent need, could fight for its paper counterpart on the market.

He “fought” not for long. Soon, a wave of rejection of payments in gold coins in favor of gold bars and currency spread across the world market, and the minting of the “Sower” was stopped.

Chervonets returned in 1925 as test copies - one copper and five gold, two of which are kept in the Pushkin Museum, and the other three in the Goznak Museum. This appearance was isolated, and was soon forgotten about for another 50 years.

Only in 1975, by order of the State Bank of the USSR, the minting of the “Sower” was resumed. The first edition was 250,000 coins. For the next seven years, the mint produced 1,000,000 each year. By 1980, another 100,000 copies of improved quality were released, timing their appearance to coincide with the beginning of the Moscow Olympiad. Both mints - Moscow and Leningrad - were involved in the minting, and their letter designations can be found on the edge. All Russian gold coins, including all reissues of the Sower and its prices can be viewed in our catalog.

After the collapse of the USSR, the chervonets remained a means of payment for the next seven years, but on January 1, 1999, it experienced another decline, losing its status as a currency. And he returned again in 2001, by decision of the Bank’s Board of Directors, regaining its legal status as a means of payment. Currently, “Sower” has become one of the four investment coins of the Bank of Russia.

Discounts, promotions and wide range

We will offer guaranteed best deals and a flexible approach to all transactions.

A rich assortment of copies of banknotes, coins, and medals will be a pleasant find for you. Items purchased from us will make your collections more complete and vibrant. A convenient and affordable system of discounts will make your purchase more profitable. The friendly communication of our consultants and the availability of a large assortment will help you make the right choice, and promotions and bonuses will make your purchase more enjoyable. You might be interested in the coin sale.

The years 1919-1921 went down in the history of Soviet Russia as the period of “war communism”. Its essence was that the state (the only owner in the country, which began to own all property) paid for work and services not with money, but directly with goods and products (rations).

Under the conditions of “war communism,” it was believed that the transition to socialism entailed the abolition of the monetary system. By the end of 1920, money functioned mainly in the private market. At that time, proposals were put forward to replace banknotes with “personalized labor cards, pay books,” “cheques,” etc. The preparation for the liquidation of the entire monetary system was also connected with the fact that even the very name of banknotes was abolished - instead of “credit notes” they began to be called “account notes”.

The transition to NEP - the “new economic policy” - demanded a return to the great economic invention of mankind - money and, as a priority, put forward the task of stabilizing finances and strengthening the Russian monetary unit - the ruble.

Speaking on November 13, 1922 at the IV Congress of the Comintern (Communist International), V.I. Lenin said that the period of stability of the ruble exchange rate in 1921 was only three months, and in 1922 - five months.

In his report, V.I. Lenin said: “First of all, I will dwell on our financial system and the famous Russian ruble. I think that the Russian ruble can be considered famous, if only because the number of these rubles now exceeds a quadrillion. What is really important is the question of stabilizing the ruble... If we manage to stabilize the ruble for a long period of time, and then permanently, it means we have won. Then all these astronomical figures - all these trillions and quadrillions - are nothing. Then we will be able to put our economy on solid ground and develop it on solid ground” (1).

In those conditions (as well as now), the issue of “hard” currency was of decisive importance for the country’s economy. In April 1921, a prominent financial figure Z.S. Katsenelenbaum, reporting at the Institute of Economic Research of the Supreme Council of National Economy on the basic principles of regulating money circulation, proposed moving towards creating new money rather than correcting old ones. He believed that the new monetary unit should be associated with precious metals (preferably gold), but the release of gold coins into public circulation seemed inappropriate to him at that time. Simultaneously with the introduction of new money, in his opinion, “monetary taxes should be established, the payment of which is obligatory in this money.” As Z.S. himself recalled in 1926. Katsenelenbaum, his proposals, which at the beginning of the summer of 1922 seemed to be an unfounded passion for “psychological theory,” were basically correct and were justified in the practice of the chervonets.

At the beginning of 1922 V.V. Tarnovsky, who before the revolution was a director and member of the board of the Siberian Trade Bank in St. Petersburg, and in 1922 a comrade, that is, deputy, Manager of the North-Western office of the State Bank, in the article “Issues of monetary circulation and the State Bank” expressed the idea that “due to the impossibility To achieve the stability of paper currency (that is, issued banknotes, nicknamed “Sovznaki”), it is necessary to allow the creation of a parallel currency for the needs of the national economy, placing it in such conditions that the disorder of the state economy and the instability of the state currency could not harm its stability...” .

It was “he (Tarnovsky) who, as a practitioner, proposed to Comrade Sokolnikov (G.Ya. Sokolnikov was the People’s Commissar of Finance) in 1922 the chervonets project, and the State Bank and Narkomfin began to carry out this reform. One way or another, it was Tarnovsky’s idea to spend the chervonets,” contemporaries admitted.

When in the spring of 1922 they began to discuss the issue of issuing a new stable currency, three names were proposed to designate it - federal, ruble and chervonets.

The word “federal” from the name of the country “Federation” was invented by workers of the People’s Commissariat, the expression “ruble” has long denoted a ruble in one coin, and “chervonets” in Tsarist Russia was a gold coin worth three rubles and weighing 3.46 grams (in addition, there was also a double chervonets weighing about 6.8 grams). By the way, the first chervonets in Rus' were made under Tsars Alexei Mikhailovich, Fyodor Alekseevich and ruler Sophia, but at that time they were more of a reward than a means of payment. Payment chervonets were first minted under Peter I, and the last time a Russian chervonets was issued was in 1797 during the reign of Paul I.

In addition, to designate the name of hard currency, the name “hryvnia” was assumed. This was the name given to a silver ingot in ancient Rus', which served as a monetary and weight unit. But since Ukrainian “hryvnia” were issued in Ukraine under counter-revolutionary governments during the civil war, this name was rejected.

If a new parallel currency is introduced, they usually try to emphasize its difference from the old one. When the Thaler was replaced in Germany in 1870, the new currency became known as the Mark. In Austria-Hungary, the guilder was replaced by the krone. And in Russia, during the reform of S.Yu. Witte in 1894 was supposed to replace the ruble with “Rus” - extremely rare examples of these test coins are known.

On October 11, 1922, the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR, by decree (the decree of the Council of People's Commissars had the force of law) “On granting the State Bank the right to issue bank notes,” decided to issue banknotes in gold terms, the denomination of which would be expressed in chervonets.

By the time of the October Revolution, the gold reserves of the Russian state had decreased to 1,260 million rubles. One half of it was kept in Moscow, the other in Kazan. From Kazan, gold in the amount of 30 thousand 563 poods (about 490 tons) in the form of Russian and foreign coins, circles, bars and strips worth 651.5 million rubles was transported by the White Guards first to the city of Samara, and then to Omsk. Admiral Kolchak and Ataman Semenov spent about 240 million rubles, and the rest was recaptured from the Whites and returned in 1920.

The first 200 thousand paper chervonets, according to the balance sheet of the Issue Department of the State Bank on November 28, 1922, were fully backed by pre-revolutionary gold coins, the so-called “imperial mintage,” of 5 rubles, 7 rubles 50 kopecks and 15 rubles in the amount of 303 thousand 500 pieces. In addition, the free balance of the emission right of 314 thousand 653 chervonets was secured by gold bullion (pure gold 333 thousand 803 spools 56 shares) in the amount of 183 thousand 591.7 chervonets, foreign gold coins worth 22 thousand 936.3 chervonets and banknotes of the Bank of England in 125 thousand pounds sterling at the rate of 0.865 chervonets per pound.

Chervonetsy, unlike sovznak, were issued not to cover the budget deficit, but for the needs of economic turnover in the interests of regulating monetary circulation. By law, paper chervonets were backed by at least 25% with precious metals (platinum, gold and silver) and foreign currency at the gold rate, and 75% with easily marketable goods, short-term bills and other obligations.

The release of chervonets into circulation was limited by law in strict accordance with the volume of trade turnover. Chervontsi were credit money and, by law, were not a means of payment. Therefore, the following inscription was placed on the front side of the paper chervonets: “The bank note can be exchanged for gold. The beginning of the exchange is established by a special government act. Bank notes are backed in full by gold, precious metals, stable foreign currency and other assets of the State Bank. Bank notes are accepted at their face value in payment of government fees and charges levied by law in gold.”

The decree on the issue of the chervonets did not establish any value relationship between it and the sovznak. Therefore, maintaining the chervonets exchange rate at the level of gold parity consisted of establishing approximately the same price in Sovznak for one chervonets and the royal gold ten-ruble notes. On November 28, 1922, at the first quotation of the chervonets, the State Bank valued it at 11 thousand 400 rubles in banknotes of the 1922 model, while the cost of a gold ten on the private “free market” was 12 thousand 500 rubles. Subsequently, the royal gold coin began to be valued cheaper than the chervonets, even paper ones, which was even reflected in fiction. “Is it okay that I have gold tens? - Father Fyodor hurried, tearing the lining of his jacket. - I’ll accept it according to the exchange rate. Nine and a half each. Today’s course,” wrote I. Ilf and E. Petrov in the book “Twelve Chairs.”

By the resolution of October 26, 1922, “Missing gold chervonets,” the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR invited the People's Commissariat of Finance to begin producing gold coins, the denomination of which would be expressed in chervonets.

On August 4, 1922, the Currency Administration of the People's Commissariat of Finance proposed to the Petrograd Mint, in connection with the upcoming issue of banknotes in gold terms, to urgently produce a sample of a gold coin and submit it for approval to Moscow. Since this requirement was unrealistic, the Mint had to politely teach the Moscow authorities.

On August 8, 1922, the plant sent a request to Moscow about what inscriptions must be placed on the proposed gold coin sample, both on one side and on the other. At the same time, it informs that the artistic decorations will be made by an artist-medalist of the Mint. The deadline for completing a coin sketch (drawing) is one week. As for the production of a sample of a completed coin, firstly, the model must be developed in accordance with the requirements of coin making, and secondly, the sample itself, according to the technical conditions, can be produced no earlier than in two months. The fact is that before the actual minting, at least of just a sample, it is necessary to prepare queen cells on a stamp-cutting machine, transfer stamps to them and carry out a whole series of intermediate and subsequent work.

On August 11, the Monetary Administration informed Petrograd that the sample coin should contain the following inscriptions: “One chervonets”, “R.S.F.S.R.”, the slogan “Proletarians of all countries, unite!”, as well as the coat of arms of the RSFSR. , because by that time the Soviet Union had not yet been formed. On the edge (rim) of the coin, the Monetary Authority asked, if technical conditions allow, to depict the weight of pure gold in the coin.

At first it was planned to release several types of gold chervonets with different designs. So, one of the types was supposed to depict a worker against the background of factories and factories, the other - a worker at a machine. A special type was planned for metal chervonets, intended for their intended release into circulation in Transcaucasia.

On August 16, an emergency meeting of the factory management was held at the Mint, at which it was decided to entrust the artist-medalist A.F. Vasyutinsky to make sketches of samples of chervonets by two o'clock the next day and send them by courier to Moscow on the same day for review and approval. This is what was done: on August 17, five design drawings of the chervonets - two drawings of the front side and three drawings of the reverse side of the coin - were sent to Narkomfin. Since this letter with drawings was apparently lost in the capital, on November 13, 1922, the Mint had to send four drawings there again - two sketches each of the front and back sides of the coin.

To draw the front side of the golden chervonets, we used an image of the coat of arms of the RSFSR, created by the Petrograd artist A.N. Leo (1868-1943) in the spring of 1918. For the reverse side drawing by A.F. Vasyutinsky used an image of a peasant sower, which he made before the revolution, for the design of an agricultural medal.

For the production of the first batch of gold chervonets of 200 thousand pieces, the Mint made an estimate of 4.5 million rubles in banknotes of the 1922 model.

November 27, 1922 People's Commissar of Finance of the RSFSR GY. Sokolnikov (1888-1939), appointed to this post on November 21, recognized the obverse side of the chervonets (sketch No. 3) as satisfactory, proposed putting the year 1923 on the coin and made comments on the design of the reverse side - “the design should depict a worker and a peasant together.”

Corrected in accordance with the comments of the People's Commissar, two sketches were sent by the Mint to Moscow on December 16, 1922. However, the drawing depicting a worker and a peasant together was later developed by the artist S.N. Gruzenberg (1888-1934) during the competition for new images for the ruble and fifty-kopeck piece of the 1924 model.

The author of the drawings of both sides of the gold coin is the chief medalist of the Mint A.F. Vasyutinsky (1858-1935). He was a true master of his craft. Graduated in 1888 Academy of Arts, he was awarded a Grand Medal for his work on the competition program “Hercules Killing the Hydra” and was sent abroad to study medal and coinage in other countries.

By decision of the Academy Council of October 31, 1888. A. Vasyutinsky received the right to a four-year trip abroad for artistic improvement from January 1, 1889 (left April 1, 1889) as her pensioner. Then the period of stay abroad was extended for another year. Abroad, he visited Vienna and Munich, and then settled in Paris, where he studied with medalist Jules-Clement Chaplain (JC Chaplain, 1839-1909) and participated in numerous exhibitions. In 1891, the medals of his work were awarded an Honorary Diploma, and in 1892 he was awarded a prize for medals and jewelry.

Returning home, A.F. Vasyutinsky introduced into Russian medal art the execution of medals in the so-called French style, more realistic and elegant, with a flatter relief and more artistic decoration of the medals. From the moment of his admission to the St. Petersburg Mint on December 17, 1893 as a class artist of the 1st degree, all artistic works were performed by him personally or under his direct supervision. In particular, he personally produced samples of coin stamps and assay marks, the proper execution of which was of great national importance.

On October 27, 1908, the Russian Academy of Arts elected A.F. Vasyutinsky with his member.

Vasyutinsky was the author of most of the designs for pre-revolutionary (since 1895) and Soviet coins. He sculpted a model of the famous sports badge GTO (Ready for Labor and Defense). A major work was the development of one of the variants of the Order of Lenin model. In 1922, at a general meeting of workers and employees of the Mint on the day of celebrating the 5th anniversary of the October Revolution, the academician was awarded the title of Hero of Labor.

The first image of the golden chervonets was published in the Krasnaya Niva magazine on July 15, 1923.

Gold chervonets of the RSFSR were minted in 1923-1924. In total, 2 million 721.2 thousand units were produced. coins, including in June 1923 the first batch - 150 pieces, in August - September - 475 thousand pieces, in October - December - 1923 - 638 thousand 50 pieces. and in January - September 1924 - 1 million 638 thousand units.

The ligature (total) mass of a chervonets is 8.6026 grams (2 spools of 1.6 shares), pure gold in a coin is 7.74234 grams (1 spool of 78.24 shares). The diameter of the chervonets is 22.606 mm (89 points). Edge inscription: “Pure gold 1 spool 78.24 shares PL.” PL are the initials of the head of the coin processing department of the plant, P.V. Latyshev, who was responsible for minting coins from precious metals.

All chervonets are dated 1923, since the People's Commissar of Finance ordered this date to be put on the coin. The date is actually an official figure of the Mint and should not be approved, but the People's Commissar did not know this.

Metal chervonets were intended not so much for use in foreign trade, as some still think, but for circulation, if necessary, within the country. This is what I.O. Shleifer, an employee of the People’s Commissariat of Finance, wrote in the book “Currency Reform” (1924): “When we issued chervonets, we gave the task of minting gold chervonets. Some thought that this was being done for the outside world, that it was nice to have your own proletarian money, on which instead of the outdated face of Nicholas II there was a peasant, instead of a crown there was a factory and a plow; this pleases the proletarian heart... But the main goal of this measure is different: we decided for ourselves that if the paper chervonets slips, we announce: we will exchange the paper chervonets for gold, and by this we support the real value of the paper chervonets. Then, when we issued the chervonets, believing in victory, we prepared a gold one in case of defeat, because if you want the exchange rate of the chervonets to be stable, have a gold one, so that at any time you can say - we take paper chervonets and give gold ones.”

In connection with the production of chervonets, transactions with gold were allowed. Gold coins were allowed to be sold and bought on the stock exchange.

In the Soviet Union, a number of coins were issued into circulation, but in very limited quantities. Even the management of the Mint had to specifically ask in October 1923 the production and commercial department of the Currency Administration of the People's Commissariat of Finance of the USSR to transfer one such coin each to nine employees of the enterprise, namely: the head of the Mint A.F. Hartman, his deputy P.A. Radaev, assistant chief I.N. Zemnitsky, chief controller A.M. Linda, business manager I.S. Alikhanov, manager of coin processing P.V. Latyshev, manager of the medal department A.F. Vasyutinsky, chairman of the factory committee of trade unions V.N. Vladimirov and the organizer (i.e. secretary) of the team of the Russian Communist Party at the plant M.A. Tikhomirov.

Metal chervonets were also valued by foreigners. So, when at the Far Eastern Bank in the city of Chita, the Japanese Ambassador Mr. T. Tanaka was presented with a sample of a Soviet coin - a gold chervonets - as a gift, Mr. Ambassador put it in his pocket and declared: “I will never exchange this chervonets in my life!”

In his memories of F.E. Dzerzhinsky long-term People's Commissar of Trade A.I. Mikoyan wrote that: “at that time, gold chervonets were in circulation in the country on a par with paper ones.” At the Plenum of the Central Committee of the RCP (b) in November 1924, it was noted that in order to overcome the elements of the “free market”, it was necessary to mint gold coins. To maintain gold parity in some months of 1923-1924. it was necessary to release quite a significant amount of both pre-revolutionary and Soviet coinage onto the money market. The worsted (sewing) trust paid with gold coins to the workers of Moscow factories.

Coins were usually issued for circulation in Moscow and from there distributed throughout the country. Thus, according to the press of that time, passengers arriving in Odessa from Moscow brought with them gold chervonets. If these were royal coins, the press would not have written about it - there were enough pre-revolutionary gold coins in any city.

The release of chervonets into circulation significantly narrowed both the scope of use of Sovznaki and the sphere of circulation of royal gold coins. If before the introduction of paper chervonets, a gold coin in some places began to play the role of a measure of value and an instrument of circulation, then as the introduction of chervonets increased, the value of the golden royal ten-ruble coin decreased.

The minting of gold chervonets was also planned in 1925. They were supposed to produce, according to newspaper reports, 6 million copies. in the amount of 60 million rubles. However, as a result of the “golden blockade of the USSR” organized at that time by the bourgeois states, i.e. refusal to accept Soviet gold coins as payment for industrial goods needed by the country, this project, like the project of minting gold coins in denominations of 2 chervonets (20 rubles), remained unimplemented.

I think that the matter was limited to the trial minting of about 20 pieces of 1925 chervonets with the coat of arms of the USSR, and the 2 chervonets coins were presented only as sketches.

As a sign of protest against the “golden blockade” in Moscow, a couple of very modest demonstrations with “Down with the blockade” rallies were organized from employees of Narkomfin and banks, which did not make any impression abroad.

Therefore, in order to break the blockade, the People's Commissariat of Finance of the USSR instructed the Mint to begin, using the preserved equipment, minting pre-revolutionary coins, i.e. royal gold coins in denominations of 5 and 10 rubles. In December 1925, the plant produced 600 thousand coins of 10 rubles, in January - March 1926 - 1 million 411 thousand coins of 10 rubles and 1 million coins of 5 rubles.

It was with these coins that the Soviet Union paid abroad, and not with Soviet chervonets, which not only in Russia but also in the West belong to very rare gold coins, unlike tsarist coins, the cost of which abroad is quite moderate.

The fact that Soviet gold coins did not go abroad is confirmed by their high collection value in Western numismatic markets compared to Tsarist gold ten-ruble coins of the same weight and fineness. Thus, according to the catalog of Heinz Dietzel “Coins of Russia and the USSR since 1855” (West Berlin, 1975, 2nd edition, pp. 6 and 8), the price of a 10-ruble coin with the dates 1898-1911 was 350 marks, and the cost The chervonets of 1923 was equal to 2000 marks. Now, of course, these prices have increased several times, but their ratio should remain the same.

For the minting of royal gold coins, metal from the melting down of Soviet chervonets was apparently used. This assumption is supported by the fact that the number of minted royal coins by weight (19,441 kg) is 1,860 kg less than the manufactured chervonets of the RSFSR (21,301 kg). This difference is explained by the fact that some of the chervonets still ended up in circulation, as well as by the fumes during the melting of the coins. But I believe that no more than a few dozen metal chervonets have survived to our time. I heard about the offer of a chervonets for exchange or sale only once, those. as much as I heard about the sale of 20 kopecks from 1934 (in the mid-80s, this coin was sold in Moscow for 1000 rubles. The coin was of Leningrad origin and I have reason to believe that it was sold second-hand by the now deceased former director of the Leningrad Mint courtyard of V. L. Martynenko. The fact is that before the war there was a practice of leaving five coins for the museum of the plant, but after the war this number was reduced to two copies and a 20-kopeck coin, as well as some other rare ones, including trial ones, he took the coins for himself instead of writing them off in the prescribed manner. Let me remind you that at that time the ruble was worth 1 dollar 68 cents at the rate of the State Bank of the USSR).

Thus, the Soviet chervonets of 1923 is a very rare collectible coin and will certainly be an adornment to any numismatic collection.

___________________

¹ V.I. Lenin. PSS. 5th ed. T.45, p. 283. M. Politizdat, 1970

M. Glaser. Collector: Sat. articles. Vol. 44/Union of Philatelists of Russia, M.: 2008. -400 p.

Only proven reliable manufacturers

To manufacture products, we use only proven, reliable large and small workshops located both in Russia and abroad. All productions undergo preliminary testing, all our customers are insured against any risks. Constantly expanding the range of our offerings, we use professional equipment for minting, modeling and designing copies of coins and medals, all this allows us to regularly offer high-quality and attractive products.

For particularly sophisticated collectors, we are ready to offer interesting offers (products that are as close as possible to the original ones or made in silver or gold), including to order.

How to determine the cost yourself

Since 2001, chervonets began to be accepted in branches of Russian banks at an unstable rate, changing every day. On average, their cost for 1975-1982 is 20,000 rubles. The “Sowers” of the Leningrad MD 1981 and 1982 sell much more expensively: the first one is quite realistic to sell for 135,000 rubles, the second for 75,000.

In order to understand that you have that same treasured gold piece in your hands, it is enough to take it to any pawnshop to confirm the composition of its alloy. The hunt for the originals of 1923 is still underway. It is known that among the coins bought by the bank there may be those very “Sowers”, but so far no one has been able to find a single copy among all the copies in the bank vaults.

We will promptly collect and ship your orders

Delivery is made worldwide. We have extensive experience working with partners from near and far abroad. When purchasing from us, you can always purchase coins cash on delivery.

For numismatics collectors, we offer copies of coins of the USSR, Russia and foreign coins of various countries. Phaleristics is presented in the category “Medals, orders and awards”. For those who are passionate about bonistics, the category “Banknotes, denominations, bonds” is available. Surely many will be interested in related products and literature on collecting. We also have gifts, souvenirs and much more.

Chervonets Sower (1923-1982)

Enter “sell USSR coins” into your browser and want to know the value of the Soviet-era gold chervonets that you inherited? Our collector portal provides you with the opportunity to remotely receive free consultation regarding the sale of antiques. We also carry out a free assessment of coins using photos, which you can send to us in any way convenient for you: through mobile applications, social networks, e-mail buying coins. rus.

The history of the appearance of the Sower chervonets

The golden chervonets entered the monetary circulation of the Soviet Union in 1923. It received its name “Sower” due to the fact that the reverse depicts a peasant sowing a field. In the background you can see a plow and the outlines of factories.

This coin has a very interesting history. Its appearance is connected with the need to carry out payment transactions of the Soviet Union with Western countries, therefore, at first they were practically not involved in the monetary circulation of the USSR. But Western countries often refused to accept such banknotes, explaining their refusal by the fact that the coins depicted Soviet symbols. This problem was resolved two years later. Then the Soviet government decided to establish coinage at the Leningrad Mint on the model of the deposed Emperor Nicholas II. The fate of the golden chervonets became quite predictable: it migrated into the monetary circulation of the Soviet Union and became widespread on its territory.

Where to sell chervonets Sower

If you want to profitably sell the coin “Chervonets “Sower” (1923-1982)”, then contact the specialists of our numismatic club in Moscow. We provide accurate and fast cost estimates. The price of the coin “Chervonets “Sower” (1923-1982)” depends on the market value of gold, as well as its physical condition.

In our catalog there are special copies of Chervonets Sower coins, the cost of which is higher than others. Among these is one chervonets sower 1980. There are 2 versions of this coin: issued by the Moscow Mint and the Leningrad Mint. The designation in the form of the letters MMD or LDM is present on the edge of the coin. At the same time, the cost of the Sower LMD chervonets is slightly higher. There are also varieties according to the type of minting: regular or Proof.

The cost of chervonets coins Sower 1923 and 1925 today is quite impressive and amounts to 100 thousand rubles and more. But variants of the chervonets Sower 1976 are also in demand and highly valued, although they are among the most common. The Sower chervonets of 1982, the so-called mourning one, issued in the year of the death of Leonid Brezhnev, are also in demand.

Also, with the help of our professional numismatic club, you can sell USSR coins from other years in almost any condition. We work in St. Petersburg and Voronezh, and the purchase of coins in Moscow is carried out on the street. Yartsevskaya, Molodezhnaya metro station. Waiting for you!

We have big plans

Having been manufacturing replica coins for more than 10 years, we strive for excellence, implement interesting and complex projects, and set ambitious plans for ourselves.

The online store SUPERmonetki.ru is aimed at people who want to learn about history, memorable events, heroes of their country and individuals.

Explore our store's offerings and create your own collection of rare and commemorative coins. We hope that with our help, your passion for numismatics will bring you a lot of positive emotions.

Thank you for being with us.

Features of the chervonets model 1923

These coins were minted from 1923 to 1924 at the mint in Petrograd. The prototype of the “Sower” was the pre-revolutionary Nikolaev 10-ruble gold coin issued in 1897: the weight, diameter, metal content, as well as such parameters as gold purity were the same.

Main characteristics of the golden chervonets called “Sower”

| Aspects | Indicators |

| Weight, g | 8,6 |

| Content of chemically pure metal, g | 7,742 |

| Metal | Gold (900 purity) |

| Diameter, mm | 22,6 |

| Thickness, mm | 17 |

| Circulation, pcs. | 2 million 751 thousand |

| Type of coinage | Uncirculated |

But the appearance, or, as they would say now, the design, became completely different. On the obverse (front side) of the coin, in the very center, is the coat of arms of the RSFSR. There, against the background of the rays of the rising sun, a sickle and a hammer are crossed, around them are depicted ears of wheat, the stems of which come from a figured shield with the inscription “R.S.F.S.R.” From the shield around the coat of arms there is a circular line separating it from the inscription in a font similar to ancient Slavic script, the world-famous call “Workers of all countries, unite!” In a circle along the entire side there is a border consisting of dots.

The reverse depicts a peasant working in the field: he is barefoot, his trousers are rolled up to the knee, a basket with seeds is tied to his neck, and he throws them into the ground. A sower works against the backdrop of a hand plow, behind him the rising sun can be seen, and to the right is a factory town. The inscription “one chervonets” is placed at the top, and the year of minting is stamped in the space between the plow and the leg. Along the edge, as on the obverse, there is a dotted border in a circle along the edge.

On the edge (rib) there is a pressed inscription “1 spool 78.24 shares of pure gold” on a smooth surface.