Some historians and archaeologists believe that gold was one of the first metals with which man became acquainted in ancient times. It was quickly loved for its unusual beautiful appearance and ease of processing. It was relatively easy to mine, since alluvial gold was found in many places on our planet. Therefore, it is not surprising that in the most ancient states of our planet they began to mint gold coins in order to be able to conduct trade transactions with other powers. It was possible to create payment elements of high value from gold with small volume and weight. The safety and durability of gold money added to its advantages, which over time brought it the reputation of being the most stable items for paying for goods and services.

For several centuries, gold coins were the lifeblood of the world financial system, but by the beginning of the twentieth century the situation had changed dramatically. Nowadays, money created from a precious gold alloy is already a subject of interest for collectors and investors, but hardly anyone wants to pay with it for goods and services. Let's find out about the amazing path a gold coin has taken from the title of precious money to the status of a collectible curiosity.

Darik and Sigl

Persian Empire, late 6th century BC. e.

1 / 2

Darik. Around 375–340 BC. e. Wikimedia Commons

2 / 2

Sigl. Around 520-505 BC. e. Wikimedia Commons

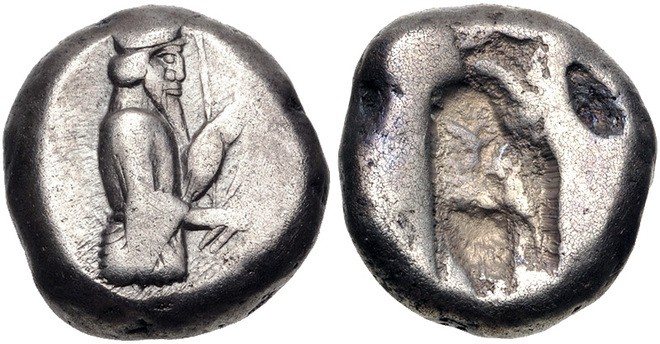

Nobody knows exactly who and when first invented money. Artifacts that performed one or more functions of money: a universal equivalent, a means of payment, a means of storage - existed almost from the very beginning of human history. The first coins are believed to have begun to be minted in the 7th–6th centuries BC. e. Alyattes, king of Lydia (present-day Western Türkiye). Soon Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire, conquered Lydia (its last independent ruler was the son of Alyattes, the famous Croesus) - and began the spread of this ingenious invention throughout his vast possessions.

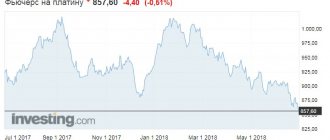

By the end of the 6th century BC. e., under Darius I, a full-fledged monetary system had already been formed in the Persian Empire. It included silver sigils (about 5.5 grams; the biblical shekel, or shekel, is a word of the same root) and gold dariks (about 8.5 grams). Darius decreed that the darik should be equal to 20 siglas, that is, the system was based on a bimetallic standard - a fixed ratio of the prices of two metals. Thus, the ratio of gold and silver prices was about 1:13 (later gold rose in price very slowly - by the 19th century the ratio reached 1:15.5).

The Greeks usually called Persian dariks and siglis "archers" because they were stamped with an image of a warrior with a bow. In the 4th century BC. e. The Persians bribed the Athenians and Thebans to attack Sparta and force the army of the Spartan king Agesilaus to leave Persia. According to Plutarch, Agesilaus, in response to this, joked that the Persian king was expelling him with the help of ten thousand archers Plutarch, “Agesilaus” (XV)..

The siglas competed, including within the Persian Empire, with Greek silver coins - drachmas. But the Greeks almost never minted gold coins. When Philip of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, finally began minting his own gold coin, the Greeks nicknamed it “Philip’s Daric.”

Dariks were readily accepted everywhere from Greece to India and are sometimes called the first international reserve currency. The minting of dariks ceased with the defeat of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great. However, his new gold coin, stater (“weight”), was an imitation of the darik in size, weight and purity.

Design

Characteristics of the 1841-1907 American Double Eagle gold coin

Metal: gold. Sample : 900. Weight: 33.43 grams. Denomination: 20 US dollars. Diameter: 34 mm. Thickness: 2.41 mm. Edge: ribbed. Quality: Unc.

Did you know? California gold was not large nuggets, but gold dust or flakes that were found in rivers. Stores, saloons, and dance halls accepted a "pinch of gold dust" as a means of exchange if coins were in short supply. For this reason, men with large hands were popular as bartenders on the country's western frontier.

Obverse: The obverse features a portrait of Liberty in the Greco-Roman style, designed by William Kniss. The woman's head is turned to the left, on her head is a crown with the inscription LIBERTY, her hair is gathered in a bun. There are 13 stars along the edge - according to the number of US states in 1841. 20 Dollars 1882 in our catalog of American gold coins. Reverse: The reverse side depicts the heraldic symbol of the United States - a bald eagle holding a ribbon. The inscription on the tape reads "E PLURIBUS UNUM".

Solid

Roman Empire, 4th century AD e.

Solidus of Emperor Valentinian II. 375–378 Yorkshire Museum / Wikimedia Commons

The Roman monetary system, especially during the Late Empire, was very complex: gold, silver and copper coins, imperial and local, coins of various emperors and usurpers, recognized by some and not recognized by others... The situation is especially confusing began after the so-called crisis of the 3rd century - a period of incessant wars and the collapse of the state. Emperor Diocletian (reigned from 284 to 305), in order to restore unity and order, had to carry out reforms that changed the empire almost beyond recognition. One of them was the introduction of a new imperial gold coin, the solidus. The coin came into widespread circulation already under Diocletian’s successors, primarily under Constantine the Great, and now the solidus is associated primarily with his name.

The Konstantinov solidus weighed about 4.5 grams and was minted from the purest gold. Its widespread distribution and persistence helped to more or less stabilize prices in the empire, and with them public finances. The very name solidus (Latin for “solid” - from the same word “solid” and “solidarity” come) was supposed to emphasize its reliability.

The gold from which solidi were minted was mined in the eastern part of the Roman Empire. With its final collapse in the 5th century, gold coins in the West almost disappeared. The barbarian kingdoms and the empire of Charlemagne had to be content with silver money. In the East, in Byzantium, the minting of solidi continued - there they were called nomismas (Greek νόμισμα - “coins”, “currency”). Over the next five centuries, nomismas (in the West they were called bezants, from the name of Byzantium) were the main currency of the Mediterranean. It was in imitation of them that the Arabs began to mint gold dinars from the end of the 7th century.

From the 11th century, Byzantine emperors, mired in ruinous wars, began to reduce the gold content of nomisma. As a result, already in the 13th century, it depreciated so much that the Italian city-states, prospering thanks to Mediterranean trade, had to start issuing their own stable gold coins - florins and ducats.

From the Latin name solida came the designations of several later monetary units, including the French sols (aka sous) and the Italian soldos. In addition, in the Old French language, the word “balance”, derived from “solid”, began to refer to the balance of payments, as well as payment to hired soldiers - soldiers.

Florin and ducat

Florentine and Venetian Republics, XIII century

1 / 2

Florin. 1374–1438 Numismatica Varesi

2 / 2

Venetian Ducat. 1400–1413 Wikimedia Commons

With the collapse of the Roman Empire, the flow of gold into Western Europe greatly decreased. The minting of gold coins did not stop, but their circulation was so small and their price so high that they were practically useless in trade. European monetary circulation relied entirely on silver. However, by the middle of the 13th century, trade in Italy had grown so much that merchants had to handle huge quantities of silver, and their storage and transportation became a serious difficulty. At the same time, thanks to eastern trade, Italian merchants became relatively rich in gold. The only difficulty was that the richest Italian cities were dependent on the Holy Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Empire was a supranational union of Italian, German, Balkan, Frankish and West Slavic states and peoples, founded in 962 and considered as a direct continuation of the ancient Roman Empire (the western part of which collapsed in the 5th century) and the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne, whose authorities did not want to share with them the monopoly on coinage.

However, in 1250, Florence, as a result of another uprising, ceased to obey the emperor. Already in 1252, the florin began to be minted there - the first mass-produced European gold coin since the time of the solidus of Constantine the Great.

The florin contained about 3.5 grams of almost chemically pure gold and replaced the silver lyre (this is a measure of weight - the Italian pound, about 329 grams). In 1284, Venice began minting its own gold coin based on the florin. The name ducat (“duke’s coin” or “doge’s coin”) was assigned to it. Florins spread throughout Europe mainly thanks to loans that Florentine bankers (the Scali, Bardi, Peruzzi families, and from the 15th century - the Medici) provided to European aristocrats and kings, and ducats - thanks to Venetian trade in the Mediterranean. As a result, the north of Europe, when minting its money, was more likely to be guided by the Florentine coin, and the south and the Middle East - rather by the Venetian one, although in essence there was no difference between them.

During the 14th century, in Germany and the Netherlands, guilders began to be minted based on the florin (from gulden - “golden”), and English and Hungarian imitations of the florin even retained the same name (the name of the modern Hungarian currency, the forint, goes back to it). In the Ottoman Empire, which was the largest trading partner of Venice, in the 15th century they began to mint sultani - an imitation of the ducat.

The production of Florentine florins ceased in the 16th century, but the Venetian ducat lasted until 1797, when Napoleon destroyed the Venetian Republic. The most impressive thing about the history of the ducat is that at the end of the 18th century it had the same gold content and the same appearance as when it appeared in the 13th century. It was not shaken by any economic and political upheavals of these five turbulent centuries, and it was against it, as an indisputable standard, that the rates of other currencies in Europe and the Mediterranean were measured. Thus, it can be argued that the Venetian ducat was the most stable currency in world history.

Illinois coin

Some archaeologists claim that the legend about the Lydian coin (statir) is incorrect. In world archeology, there is a strange story about how an ancient metal plate similar to a coin, which was only a few decades old, was discovered in the USA.

The story goes: in Illinois in 1870, while drilling an artesian well on Ridge Lawn, one of the workers, Jacob Moffitt, came across a round plate of copper alloy. The thickness and size of the plate resembled the American coin of that time, equal to 25 cents.

Pesos

Spain, XV century

Pesos. After 1497 Wikimedia Commons

When Europeans, represented by Vasco da Gama, discovered a direct sea route to India in 1498, they expected profitable trade, but found that they had nothing to offer eastern merchants. Europe was then a backwater of the world economy and did not produce anything that would interest Indians.

Around the same time, Spanish conquistadors conquered Mexico and Peru. By the middle of the 16th century, in what is now Bolivia, they discovered several huge deposits of silver, including the famous Potosi, or Cerro Rico (“Rich Mountain”), consisting almost entirely of silver ore. Silver was in constant demand in the East, and it was this that flowed there from the West in exchange for silk and spices.

At mints built right next to the mines, the Spaniards minted pesos (Spanish pesos de ocho, literally “peso-eight”: 1 peso was exchanged for 8 reais) - large silver coins modeled on the German thaler (weight - 28-29 grams, purity - about 80%). From the New World, pesos spread around the world in two huge streams: the first - across the Atlantic Ocean to Seville and from there throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, as well as to India along the route laid by Vasco da Gama; the second - across the Pacific Ocean to China and the islands of the Malay Archipelago. On the second route, the main transshipment point was Manila in the Philippines, founded by the Spaniards in 1571 - from that moment on, flows of silver surrounded the entire globe and trade became truly global.

By the end of the 16th century, Spanish pesos-octets, minted in Mexico and Peru, had become the most common silver coin in the world. They were used to pay everywhere - from Jamaica to Java and from Arkhangelsk to the Cape of Good Hope. It was the first truly global currency. It remained in this status until the end of the 18th century.

The coin had many names in different languages. For example, in English it was called either a piece of eight (the literal translation of the phrase peso de ocho, that is, “a piece of eight [reals]”), or a dollar (a distorted “thaler”); in Chinese - shuangzhu (“two pillars”, after the image of the Pillars of Hercules on the Spanish coat of arms, which was minted on a coin); in Italian - piastra (translated as “tile”, “ingot [of silver]”). From this last name comes the most popular Russian name for the peso-octagon - piastre.

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages and until the Renaissance, the medal art of Europe was undeveloped: the coins had a flat relief, the coin itself was thin and looked like a metal plaque. True, there is an exception to this rule.

In the German states of the 12th century, coins were still of high artistic quality. And such bracteates flourished during the time of Frederick I Barbarossa.

Stamps for coins were then made by professional engravers. The coins even reflected the style of that era - they can be attributed to late Romanesque art. The coins depicted figures of rulers and saints in a symmetrical frame of architectural elements. Although the figures were stylized, the small details on them were carefully worked out - armor, clothing, attributes of power.

Guinea

England, 17th century

Two guineas of Charles II. 1664 Wikimedia Commons

In 1660, the only experiment with republican rule in English history ended: after two decades of civil wars and political chaos, the king returned to the country. This was Charles II Stuart, son of Charles I, who was executed in 1649. The new monarch was in a hurry to erase all memory of the time when the country was ruled by the murderers of his father. In particular, he was impatient to force the money minted by them out of circulation and replace it with new ones, with his image. The problem was that the Royal Mint was constantly experiencing a shortage of raw materials. England's own natural reserves of silver were small, and it was unprofitable to mine it, since the market was flooded with cheap silver from the Spanish colonies in America. England did not have its own gold deposits at all. That is, in order to mint coins, it was necessary either to buy metals abroad or to buy back old coins from one’s own population.

Soon after his accession, Charles established the Company of Royal Entrepreneurs trading with Africa. It quickly unfolded in Guinea, a region in western Africa from which Europeans exported slaves, ivory and gold. Charles began minting a new coin from Guinean gold, called the guinea.

The history of English money in the second half of the 17th and early 18th centuries is mainly the history of the struggle to preserve the bimetallic standard, that is, a monetary system based on a solid ratio of gold to silver. In Amsterdam, then the world center of foreign exchange transactions and trade in precious metals, one weight unit of gold was equivalent to 15 units of silver. In England, gold was valued higher - at least 15.5 units. This was mainly due to the fact that there were a huge number of old, roughly hand-minted silver coins in circulation (many of them were issued 40, 50, or even 100 years ago), worn out and cut off at the edges, as well as counterfeits. No one trusted silver money, while guineas, relatively rare and well protected from counterfeiting (they were minted by machine), enjoyed universal trust and therefore traded at a premium to the nominal price.

The guinea had a denomination of 1 pound sterling. The pound sterling was an English monetary unit, originally (around the 11th century) literally a pound (just over 450 grams) of small silver coins called sterling. Under Charles II, it actually contained only about 120 grams of silver (a pound was equal to 20 shillings, each coin contained approximately 6 grams). (20 silver shillings), but in fact it was never paid for less than 21 shillings. This meant that if you melted silver money into bullion, took it to Amsterdam and sold it there by weight, you could make a profit of five percent minus production and transport costs (silver was more expensive as a commodity than as English coins). By the 1690s, the guinea had reached 30 shillings. Profits from the export of silver from England increased so much that the silver money leaving the Royal Mint in the Tower often did not have time to cool before it was melted down to be sent to Amsterdam.

The next attempt to save English bimetallism was the Great Recoinage of 1696: the treasury bought old silver money from the population at the market rate, and in return issued new, full-weight, machine-made ones. After recoining, the guinea rate dropped from 30 to 22 shillings. The mint at this time was headed by Isaac Newton. In 1717, he proposed legislation to prohibit the exchange of a guinea for more than 21 shillings. But even after this, a unit of silver in the Netherlands or France was still worth more than in England, and its outflow never stopped. The English government abandoned further attempts to establish a fixed ratio of gold to silver and actually switched to the gold standard (however, this was legislated only a century later).

The minting of guineas ceased in 1813, and in 1817 the £1 sovereign was issued as the new standard gold coin. However, the guinea survived as a unit of account equal to 21 shillings (1.05 pounds) until the pound was converted to decimalization in 1971. It is precisely as a counting unit that it is found every now and then in Victorian literature, including in the stories about Sherlock Holmes.

Efimok with a sign

Russia, XVII century

Efimok with a sign. 1655 Coinage on a 1637 thaler Wikimedia Commons

The main problem of monetary circulation in Russia since ancient times was the lack of its own precious metals. There are no large deposits of either gold or silver on the East European Plain, and Siberian deposits began to be truly developed only in the mid-18th century. Before this, money was minted only from imported silver. In the 16th–17th centuries, as a rule, it was brought in the form of thalers - large European coins with which foreign merchants paid for Russian export goods. The oldest of these coins was the Joachimsthaler from the beginning of the 16th century. The last Joachimsthaler was minted in 1528. In Russia it was nicknamed efimko. The same name subsequently spread to other thaler coins. The most famous thaler coin is the piastre. Thaler coins were also minted by Lubeck and Hamburg (cities included in the Hanseatic Trade Union), England (silver crown). The Dutch Levendalder was formally also a thaler coin, but in fact it had a lower standard and was valued lower. Silver came to Russia mainly in the form of a variety of North German thaler coins and Löwendalder coins.

At Russian money courts, efimki were melted, and kopecks were minted from the resulting silver (the ruble existed only as a unit of account; in physical form it was represented by a pile of 100 kopecks). An average of 64 kopecks came out of one efimka. At the same time, the official exchange rate from the middle of the 17th century was 50 kopecks per efimok - the difference was the treasury’s profit.

In 1654, under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, a major monetary reform was carried out in Russia: copper pennies began to be minted, and a silver ruble was introduced on the model of the thaler. The problem was that the ruble in the old silver kopecks, which still formed the basis of circulation, contained about 47 grams of silver, while the new ruble contained only 28–29 grams. The commodity price of old money turned out to be significantly higher than the nominal value, and people began to hide them. The new ruble turned out to be unviable.

Already in 1655, the tsar's advisers invented a new technique: thalers were not melted, but were simply minted with a penny stamp (this was called a “sign”) and issued into circulation at a face value of 64 kopecks. At the same time, the treasury did not lose anything, saving on waste (loss in the weight of silver during smelting) and on the wages of money masters.

However, the efimok with the sign also did not last long: copper money soon almost completely replaced all silver from circulation, prices began to rise, and it ended with the Copper Riot of 1662 and the abolition of all innovations in the monetary sphere. The ruble, modeled on the thaler, appeared in Russia only half a century later on the initiative of Peter I.